|

His next stop on this

European journey was naturally Paris, about which he had learned an enormous

amount, and where many of the modern art movements he had studied had

originated. He had been taught that Paris was a shining example of enlightened

urban renewal under Baron Haussman, but found that he preferred the complexity

and scale of the Marais to the grandeur and uniformity of the façades

lining the boulevards driven ruthlessly through the mediaeval plan. It

was quite clearly better than the deadly grid imposed on the centre of

Lisbon, but behind the façades along the boulevards and squares,

the quality deteriorated and the planning of Barcelona seemed to offer

a much more interesting model. But Paris, and especially the Louvre, was

a stimulating experience and even at that depressed post-war period there

were many small galleries and bookshops where he browsed and bought a

few prints and many books to take back. In one of them he discovered the

work of Victor Brauner, who remains one of his favourite artists.

Le Corbusier,

based in Paris, was at that time the moving spirit behind CIAM, but younger

architects were later to rebel against the dogmas and worn out pre-war

ideas of the ‘heroic’ phase of the Modern Movement. Eight years later

Pancho was invited to come to the inaugural meeting of Team 10, which

was formed by a group of dissidents from CIAM : Aldo van Eyck, Alison

and Peter Smithson, James Stirling, Jacob Bakema, Shadrach Woods, Georges

Candilis, Alexis Josic and others. This first meeting was at Royaumont,

near Paris in 1962, and was the start of a long association with Team

10.

At

these quite informal meetings, architects presented their work, which

was discussed by the others. Pancho did not have a great deal in common

with them, apart from his dislike of what CIAM represented. But he was

always very well received, because they recognised the originality of

his work, especially his architecture, and appreciated the clarity of

his criticism which was, as always, delivered without giving offence.

He felt, all the same, that he belonged to a different world. Most of

the architects who attended Team 10 worked in a milieu terribly constrained

by regulations, conservative demands for preservation and conformity to

the character of existing buildings. They were much concerned with issues

of social progress, of equality, repetition and the uniformity that came

with industrialisation, and a building industry that distanced the architect

from the process on site.

They

envied him his freedom to be creative and ability to carry out his projects

free from official bureaucratic constraints. Another difference was the

simplicity of building construction in Mozambique, and predominance of

craft techniques, in which he could be closely involved with the execution,

sometimes working himself on site, setting out or painting murals. He

maintained his contacts with Team 10 members and there were meetings in

London, Berlin, Lisbon, Barcelona, Perugia and some of them even travelled

to Mozambique to see his work. Despite their differences, he learned something

from them and their special guests, like Louis Kahn, that began to have

an effect on some of the buildings he designed during the sixties. He

coined the term ‘American Egyptian Style’ to describe some of Kahn’s work,

in an article he wrote for ‘World Architecture 1’ edited by John Donat,

and then went on to use the term for some of his own buildings with pyramidal

roofs and formal symmetrical plans. Examples are the ’Yes House’ and the

pyramidal kindergarten.

|

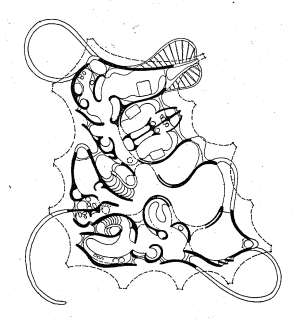

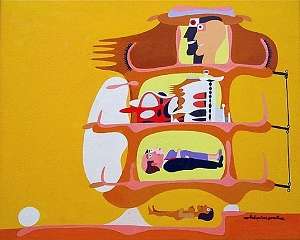

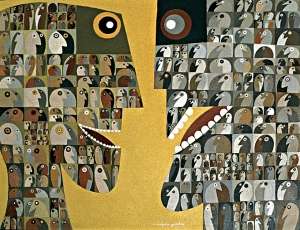

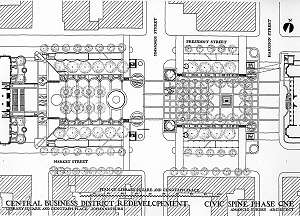

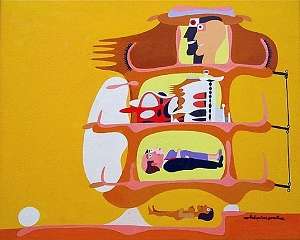

Guedes - Painting based on 'Smiling Lion' apartment section

- 1982

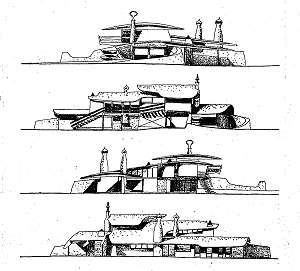

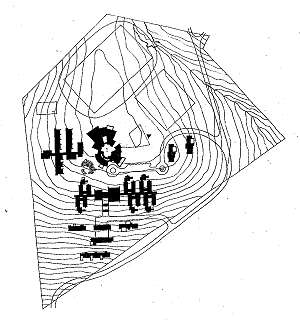

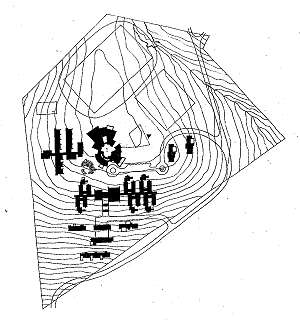

Guedes

- Waterford School, Swaziland, Site Plan : 1963 - 1972

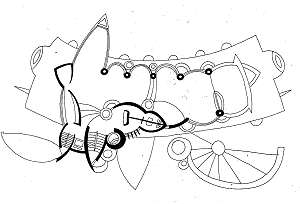

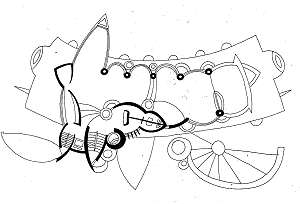

Guedes

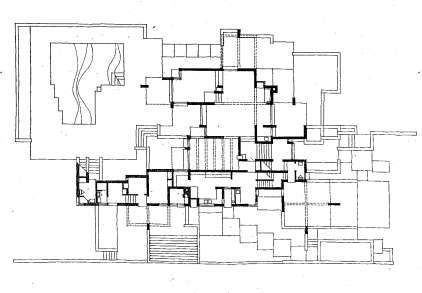

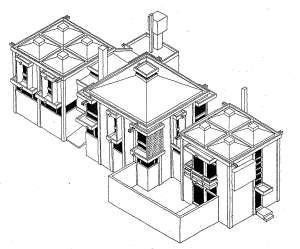

- Hotel at Reuben Point, Lourenço Marques : 1952

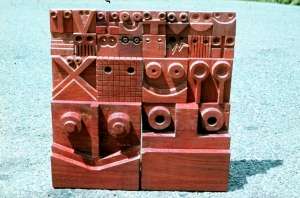

Guedes - Salm House, Lourenço Marques - 1963 -1965

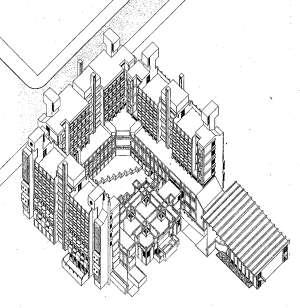

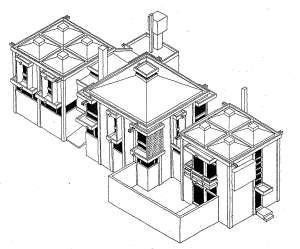

Guedes - 'Yes House', Lhanguene, Lourenço Marques : 1961

- 1962

|