PANCHO GUEDES : THE EYE HOUSE

Timothy Ostler

|

The Serra de Sintra , thirty miles north-west of Lisbon, is one of Portugal's greenest and most beautiful areas. Rain coming in from the west, unable to escape through the solid granite subsoil, instead trickles down the mountain through the topsoil, ensuring a lushness and exoticism of plant life quite unique in the region.

Sintra's architecture, too, is noted for its alien quality. Over the years, kings and caliphs attracted by the climate have adorned its slopes with numerous extravagant and eclectic palaces.

The most recent contribution to this cosmopolitan mix comes from Pancho Guedes, already the author of over five hundred buildings in Moçambique, as well as innumerable paintings and sculptures. The tiny cottage Casal dos Olhos, built in Eugaria (an exquisite village a few miles west of the town of Sintra) for his daughter and grand-daughter, although making liberal use of traditional motifs and details, frequently turns them on their heads.

It could never happen here. Planners here tend to take a very literal view of what is 'in keeping'. In Sintra's eclectic context, however, such an attitude is hard to sustain.

|

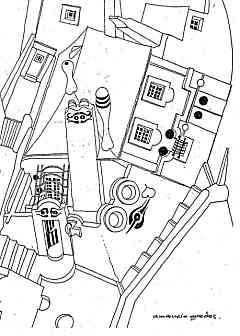

| "cubist" multiple elevation drawing |

The Eye House is only the most recent example of Guedes' customary practice of merging his art with his architecture. It has been a notorious habit of his ever since the fins and spikes of his 'Smiling Lion' apartment block built back in the fifties - in elevation almost a built realization of Dali's 'Architectural Angelus.' For Guedes it is nothing new to individuate a design with one (in his words) 'intense' central theme or image. But why this obsession with eyes?

Guedes' story is that for a long time he had been fascinated with the winged eye on Alberti's famous medal - since the 1950s, in fact, when the Architectural Review published a special issue called The Seeing Eye, taking it as their symbol. Then, during research on Portuguese squares, Guedes acquired a fixation for the eyes Portuguese fishermen paint on their boats. These personal obsessions merged with the design while Guedes was sketching in a friend's house in Carcavelhos. Perhaps the traditional chimney shape, with its 'eyebrows' outline, also suggested the theme.

Guedes does not believe in overdesigning. Motifs that recur at a detail level are usually very simple. At the Eye House, linked perhaps with the ocular theme, it is a kind of hide and seek produced by opening and closing windows, shutters and doors. Guedes intends to paint the shutters to show two eyes looking out of the windows which disappear when they are opened. Paintings are hung so as to be obscured by open doors. A set of brassed lead railway cap badges are brassed and screwed to the entrance door frame, to be revealed as the door is closed.

The sliding sash windows, made in the north according to a simple standard pattern, are held open by folding brass sash props rather than cords or weights. A seat is built into the wall underneath the window in the traditional manner. The deep blue of the elevations is also customary in the area, as a means of warding off evil spirits.

Guedes' is a narrative architecture. It is evident that he does not see its practice as being carried out in a vacuum, as his account of each job is closely concerned with the personalities and often outrageous events involved over the months from inception to completion - and beyond. Nothing relevant is omitted, from the state of the clients' marriage to the content of the contractor's dreams.

The machinations and complications behind the building of this tiny house were probably as great as for any other building with which Guedes has been involved - including one job when his contractor took to wearing a gun on site. Construction was carried out during short hectic working holidays spread over a period of four years. The first few days of each visit would invariably be spent breathlessly organizing contractor or subcontractors, with the remainder spent working night and day, either on construction or travelling around Portugal in search of a particular component or item of furniture.

The main supplier was a small time builder who according to Guedes coveted the house, brushing aside the architect's intermittent financial difficulties, crying 'Take credit, take credit! …Then if you don't pay me I'll take your house!' Guedes, in the habit of visiting him early in the morning in order to catch him in his pyjamas, says 'he and his assistant are perfectly convinced that I'm mad.'

The house already had two 'cock-eyed' windows with mouldings, a door downstairs, and a little porthole side window, with no connection between the two floors, (animals were kept in the basement). The top of the house was demolished and rebuilt after the large garage opening was formed. Guedes spent a great deal of time refining the main elevation, adjusting the proportions of the elevation by building a false wall on the outside up to first floor level. This had the effect of accentuating the base and articulating the façade, producing 'one form piggy-back on the other.'

The composition was thus fragmented into three parts: the blue wall enclosing the courtyard, with its two eyes, the downstairs section in a darker blue, and the white area above, with two windows. Guedes felt that he had to shift these two upper windows away from the ground floor and from each other, again making a large number of sketches. He then hit on the idea of semi-circular forms 'hanging' from the window moulding, visually weighing the windows down. The cornice moulding, was painted pink and retained.

The courtyard, fully enclosed by high walls, is a genuine external room, bisected by a pink steel trellis leading from the gate to the entrance door. Planted in a hole beside the clothes-line (here, as always with Guedes, incorporated into the design) are the beginnings of a vine. The architect hopes that this will cover the trellis within a couple of years, sheltering the table and chairs (a standard pattern of steel chair with variations of the entrance eye motif cut out of the backs). Guedes cast the twin 'oculi' using a couple of old tyres as formwork.

Plans for the bedroom, originally intended to be in the roof space above the kitchen, included a Gothic plastered bedhead. However, neighbours would not allow the existing roof to be raised, so the bedroom had to be moved instead into the basement, where both ventilation and privacy were in short supply. Guedes' answer to this was to design the window four-square with four opening lights and four hinged shutters, adjustable in any one of a number of combinations. Burglar bars were also designed to act as a louvred privacy screen.

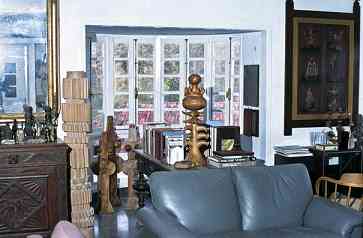

Guedes cast the slab roof directly on thick composite board laid on the sloping roof members: 'If I'd had a flat ceiling, imagine how terribly dull those spaces would have been: sort of low narrow little boxes. Like this you have quite a grand space.' The grandness is accentuated by the retention of the stairway, now leading nowhere and acting only as a formal device, lit by two ceremonial globes which illuminate the small hardwood figurines sitting halfway up the stairs.

Inside, there is extensive use of the beautiful pink marble that constitutes the landscape around Estremoz in the south-west, an area about which Guedes speaks enthusiastically: 'It's amazing. You just dig a hole - and there's marble.' It's a particularly strong variety of stone, used for all the kitchen work surfaces and table tops - Guedes has even built a marble drawing board into his rosewood desk, complete with a brass tee square.

When I saw it he had just bought two French curves which he intends to screw to the desk. Could we expect to see more scrolls in his architecture? 'No, it's just because they are very pretty - you know that I am not a functionalist.'

Contrasting strongly with the simple rosewood furniture in the living room are two Baroque church pieces which, with an angel in the kitchen, Guedes purchased in Portugal twenty-five years ago: 'St Agatha, who was martyrised by having her breasts cut off. If you see them from here they look terrific!' (he is speaking from the entrance door from which point only a hand holding what appear to be two blancmanges on a plate can be seen).

Then, pointing to the Madonna and Child on a steel cloud over the kitchen door, he says 'and you see how the Child Jesus is blessing everyone that comes into the house' … His son Pedro Guedes (practising in London with Alan Berman) insisted on the cloud: 'We had a disagreement over the cloud. I won - it's my cloud. It's a kind of sausage cloud'. It has recesses for two pink fluorescent tubes 'to throw a pink glow on the Virgin when you are watching TV.'

|

Already the first of the architect's own sculptures and paintings have been air-freighted in (as heavily overweight accompanied baggage. Affording it is easy, says Guedes: 'It is just a matter of appearing lost when the airline informs you how much excess baggage you have to pay'). After four years of intense effort, the house is at last beginning to assume the character of a repository of dilettante artefacts in which, like Guedes' own 'Red Pyramid' in Johannesburg, Sir John Soane might have felt at home.

Timothy Ostler 1986

| HOME PAGE | CONTENTS PAGE | PREVIOUS PAGE | NEXT PAGE |